Psychological Research

Developmental Research Designs

Sometimes, especially in developmental research, the researcher is interested in examining changes over time and must consider a research design that captures these changes. Remember, research methods are tools used to collect information, while research design is the strategy or blueprint for determining how to collect and analyze information. Research design dictates which methods are used and how they are employed. There are three types of developmental research designs: cross-sectional, longitudinal, and sequential.

Video 2.9.1. Developmental Research Design summarizes the benefits and challenges of the three developmental design models.

Cross-Sectional Designs

The majority of developmental studies use cross-sectional designs because they are less time-consuming and less expensive than other developmental designs. Cross-sectional research designs are used to examine behavior in participants of different ages who are tested at the same point in time. Let’s suppose that researchers are interested in the relationship between intelligence and aging. They might have a hypothesis that intelligence declines with age. The researchers might choose to administer a particular intelligence test to individuals of three age groups: 20 years old, 50 years old, and 80 years old, and compare the data from each age group. This research is cross-sectional in design because the researchers plan to examine the intelligence scores of individuals of different ages within the same study at the same time; they are taking a “cross-section” of people at one point in time. Let’s say that the comparisons find that 80-year-old adults score lower on the intelligence test than 50-year-old adults, and 50-year-old adults score lower on the intelligence test than 20-year-old adults. Based on these data, the researchers might conclude that individuals become less intelligent as they get older. Would that be a valid (accurate) interpretation of the results?

Figure 2.9.1. Example of a cross-sectional research design

No, that would not be a valid conclusion because the researchers did not follow individuals as they aged from 20 to 50 to 80 years old. One of the primary limitations of cross-sectional research is that it yields information about age differences, rather than changes over time. That is, although the study described above can show that 80-year-olds scored lower on the intelligence test than 50-year-olds, and the 50-year-olds scored lower than the 20-year-olds, the data used to draw this conclusion were collected from different individuals (or groups). It is possible, for instance, that when these 20-year-olds mature, they will still score just as high on the intelligence test as they did at age 20. Similarly, it is possible that the 80-year-olds would have scored relatively low on the intelligence test when they were younger; the researchers don’t know for certain because they did not follow the same individuals as they aged.

With each cohort comprising members of a different generation, it is also possible that the differences found between the groups are not due to age per se, but rather to cohort effects. Differences in IQ results between these cohorts could be attributed to life experiences specific to their generation, such as variations in education, economic conditions, technological advancements, or shifts in health and nutrition standards, rather than age-related changes.

Another disadvantage of cross-sectional research is that it is limited to a single point in time. Data are collected at one point in time, and it’s possible that something could have happened in that year in history that affected all of the participants, although possibly each cohort may have been affected differently.

Longitudinal Research Designs

Longitudinal research involves beginning with a group of people who share the same age and background (cohort) and measuring them repeatedly over an extended period of time. One of the benefits of this type of research is that people can be followed over time and compared with themselves when they were younger; therefore, changes with age can be measured. What would be the advantages and disadvantages of longitudinal research? Problems with this type of research include its expense, time-consuming nature, and subjects dropping out over time.

Longitudinal research involves beginning with a group of people who share the same age and background (cohort) and measuring them repeatedly over an extended period of time. One of the benefits of this type of research is that people can be followed over time and compared with themselves when they were younger; therefore, changes with age can be measured. What would be the advantages and disadvantages of longitudinal research? Problems with this type of research include its expense, time-consuming nature, and subjects dropping out over time.

Longitudinal research designs are used to examine behavior in the same individuals over time. For instance, in the context of studying intelligence and aging, a researcher might conduct a longitudinal study to examine whether 20-year-olds become less intelligent with age over time. To this end, a researcher might administer an intelligence test to individuals at the age of 20, again at 50, and then again at 80. This study is longitudinal in nature because the researcher plans to study the same individuals as they age. Based on these data, the pattern of intelligence and age might differ from that observed in cross-sectional research; it may be found that participants’ intelligence scores are higher at age 50 than at age 20 and then remain stable or decline slightly by age 80. How can that be, given that cross-sectional research has revealed declines in intelligence with age?

Figure 2.9.2. Example of a longitudinal research design

Since longitudinal research spans a period of time (which can be short-term, such as months, but is often longer, like years), there is a risk of attrition. Attrition occurs when participants fail to complete all portions of a study. Participants may move, change their phone numbers, die, or simply become disinterested in participating over time. Researchers should account for the possibility of attrition by initially enrolling a larger sample in their study, as some participants are likely to drop out over time. There is also a phenomenon known as selective attrition, which means that certain groups of individuals tend to drop out. It is often the least healthy, least educated, and those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds who tend to drop out over time. That means the remaining participants may no longer be representative of the entire population, as they are, in general, healthier, better educated, and have more financial resources. This could be a factor in why our hypothetical research revealed a more optimistic picture of intelligence and aging over time. What can researchers do about selective attrition? At each time of testing, they could randomly recruit more participants from the same cohort as the original members to replace those who had dropped out.

The results from longitudinal studies may also be impacted by repeated assessments. Consider how well you would do on a math test if you were given the exact same exam every day for a week. Your performance would likely improve over time, not necessarily because you developed better math abilities, but because you were continuously practicing the same math problems. This phenomenon is known as a practice effect. Practice effects occur when participants become better at a task over time because they have done it again and again (not due to natural psychological development). So our participants may have become familiar with the intelligence test each time (and with the computerized testing administration).

Another limitation of longitudinal research is that the data are limited to only one cohort. For example, consider how comfortable the 2010 cohort of 20-year-olds was with computers. Since only one cohort is being studied, it is not possible to determine if the findings would be different from those in other cohorts. In addition, changes that are observed as individuals age over time may be due to age-related effects or to time-of-measurement effects. That is, the participants are tested at different periods in history, so the variables of age and time of measurement could be confounded (mixed up). For example, what if there is a significant shift in workplace training and education between 2020 and 2040, and many of the participants experience a lot more formal education in adulthood, which positively impacts their intelligence scores in 2040? Researchers wouldn’t know whether the intelligence scores increased due to aging or a more educated workforce over time between measurements.

Sequential Research Designs

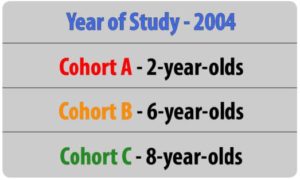

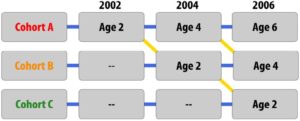

Sequential research designs include elements of both longitudinal and cross-sectional research designs. Similar to longitudinal designs, sequential research involves following participants over time; similarly, sequential research includes participants of different ages, much like cross-sectional designs. This research design is also distinct from those discussed previously in that individuals of different ages are enrolled in a study at various points in time to examine age-related changes, development within the same individuals as they age, and to account for the possibility of cohort and/or time-of-measurement effects.

Consider, once again, our example of intelligence and aging. In a study with a sequential design, a researcher might recruit three separate groups of participants (Groups A, B, and C). Group A would be recruited when they are 20 years old in 2010 and would be tested again at 50 and 80 years old in 2060 and 2070, respectively (similar in design to the longitudinal study described previously). Group B would be recruited when they are 20 years old in 2040 and would be tested again when they are 50 years old in 2070. Group C would be recruited when they are 20 years old in 2070, and so on.

Figure 2.9.3. Example of a sequential research design

Studies with sequential designs are powerful because they allow for both longitudinal and cross-sectional comparisons—changes and/or stability with age over time can be measured and compared with differences between age and cohort groups. This research design also enables the examination of cohort and time-of-measurement effects. For example, the researcher could examine the intelligence scores of 20-year-olds at different times in history and different cohorts (follow the yellow diagonal lines in Figure 3). This might be studied by researchers who are interested in sociocultural and historical changes (because we know that lifespan development is multidisciplinary). One way of assessing the usefulness of various developmental research designs is described by Schaie and Baltes (1975): cross-sectional and longitudinal designs may reveal change patterns, while sequential designs may identify the developmental origins of the observed change patterns.

Since they incorporate elements of both longitudinal and cross-sectional designs, sequential research shares many of the same strengths and limitations as these other approaches. For example, sequential work may require less time and effort than longitudinal research (if data are collected more frequently than over the 30-year spans in our example) but more time and effort than cross-sectional research. Although practice effects may be an issue if participants are asked to complete the same tasks or assessments over time, attrition may be less problematic than what is commonly experienced in longitudinal research, as participants may not have to remain involved in the study for such a long period.

Comparing Developmental Research Designs

When considering the best research design for their study, scientists think about their primary research question and the most effective way to obtain an answer. A table of advantages and disadvantages for each of the described research designs is provided here to help you as you consider what sorts of studies would be best conducted using each of these different approaches.

Table 2.9.1. Advantages and disadvantages of different research designs

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

| Cross-Sectional |

|

|

| Longitudinal |

|

|

| Sequential |

|

|